An investigation into Bristol’s History of Water Rights

Bristol is a city steeped in history, not just in the more obvious spots like the imposing and vast iron hull of the SS Great Britain, the iconic and impossible suspension bridge, nor the old industrial relics by the harbour’s wayside. In Bristol, some of the best stories are found in its nooks, crannies and alleys. And no that’s not an allusion to wandering down Hepburn Road on some misguided drunken adventure. No, in Bristol, the relics of this once Medieval city can be found in the most unassuming places.

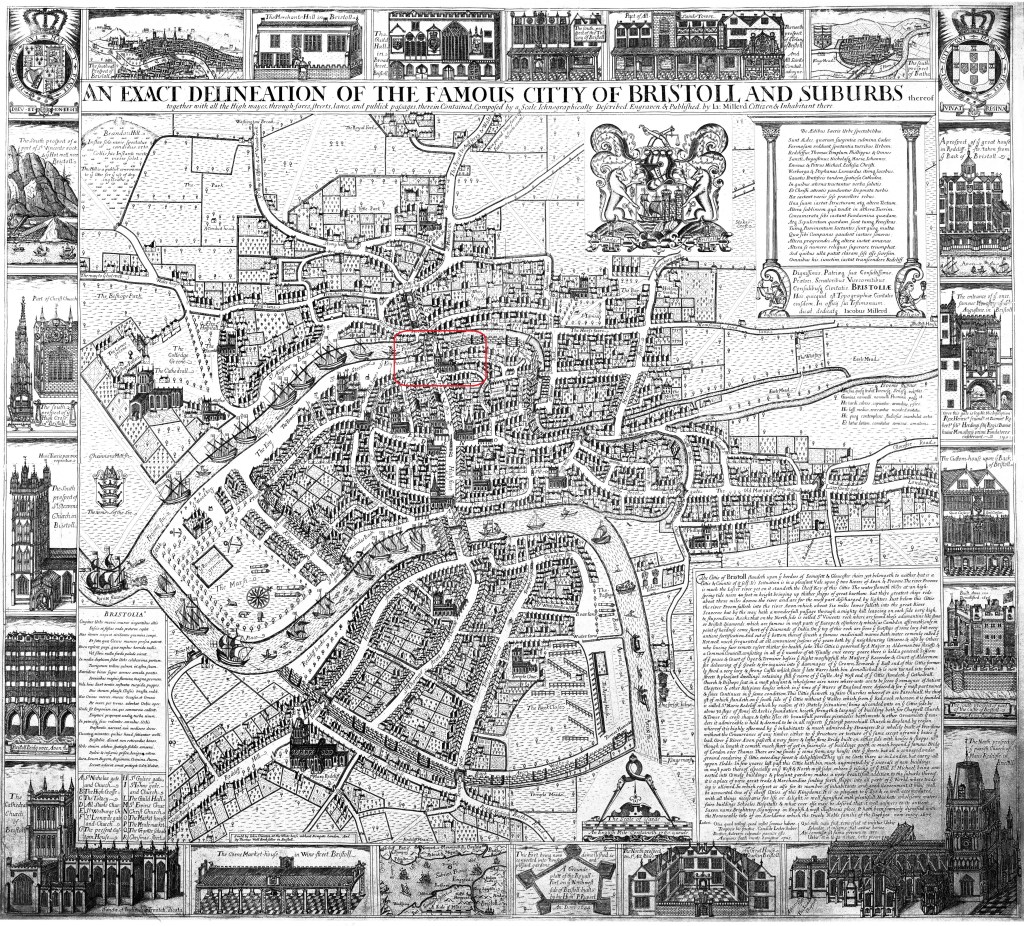

St John on the Wall or the Church of St John the Baptist, despite the name, is fairly unassuming. And while its archways are now bedazzled by murals commissioned by the city, making for a popular photo spot for tourists stopping by at one of the may adjacent hotels, the church itself is oft ignored by passers-by, owing in part to the fact that it’s usually closed to the public. But if you’re lucky enough to get into the church on one of the few days that it’s open to the public, you really become immersed in the Medieval world of Bristol. This church get’s its namesake of ‘on the Wall’ from the fact that it rests on one of the former innermost city walls of medieval Bristol, walls that delineated the boundaries of the city itself.

But moving away from this church and its place in the civil architecture of Medieval Bristol, I want to focus on a feature of this church, and the story it can tell us about Bristol, Britain and even the world, and the erosion of trust and transparency around our access to water rights. This feature I speak of is known as ‘St Johns Conduit’, and for the better part of a few years it was not visible to the public due to construction on student accommodation going on just adjacent to it. But now, even if you were walking through the busy backroad of Quay Street, the conduit itself probably wouldn’t grab your attention for too long; it’s integrated into the wall, restored in gleaming sandstone, cutting between the dark and uniform modern bricks of the aforementioned student flats, and the plethora of bricks from different cuts and colours that make up the old city wall on which the church resides.

St Johns Conduit is a water conduit that previously supplied water to the people of Bristol, drawing from a wellspring on Brandon Hill. The construction of this conduit had been dated to 1374, with the church being built slightly earlier in the 14th century. Both the church and the conduit were later re-worked and renovated in the 19th century, with this rework still visible on the façade of the Conduit, being restored by the local board of health in 1866.

Now if you were to understand the historical development of Waterworks in Bristol using Bristol Water’s website and their so called ‘social history’ of the matter, you’d be sold on a narrative that the benevolent water companies had ensured the health and wellbeing of the masses, continuing to add ‘social and economic value’ through their services all the way from 1695 until their last update in 2019.

Though, in this case, history has been told by the victor, a victor that emerged out of circumstance, seized an opportunity, and has now used that opportunity to profiteer from a public resource. In truth, the distribution of water in the Medieval era, and in the 14th century when St John’s church was built, was far more decentralised, gathered by people from wellsprings, and distributed from Conduits controlled by priories. This, of course, wasn’t entirely safe, and as the breakup of the monasteries occurred and urban populations rose, the Bristol Waterworks Company stepped in around the late 17th century to create a gravity fed waterworks system to replace the now collapsed and previously decentralised system of water distribution in Bristol.

While there’s far more of a story to tell of the development of waterworks in Bristol from the late 17th century onwards, this article more wants to look at moments in Bristol’s history to discuss how current events have unfolded. The current event I’m referring to is something that’s passed under the radar, and dumped under our noses, in the most literal sense. I’m of course referring to the rampant dumping of sewage and pollutants into our waterways and oceans by some of the largest water companies in Britain. Now this hasn’t gone completely unnoticed, and six of the Uk’s largest water companies had a civil suit launched against them in 2023 for failing to report these discharges to the Environment Agency. While not mentioned in this suit, equally culpable is the huge Water company Southwest Water. Of course that’s not Bristol water, right? Well, no, Bristol Water has been owned by Southwest Water as of February 2023, meaning that the image of an independent utility company is just a masquerade. Well then you may think that perhaps that move was made in order to save money and would lead to a better-quality service. Well, no, this coincided with over 58,000 sewage ‘spills’ from South West water alone in 2023, with further evidence of dumping in January 2024 near Exmouth.

All the above reflects a pattern, this pattern being sacrifices that have occurred uniformly across the utilities sector, and former sectors that were previously publicly owned. These sacrifices are cuts in spending, price rises, lax regulation and anything else that puts the public at expense in favour of not reducing profit margins. And this all points to one conclusion, that privatization has gotten far out of hand, for while Bristol Water tells a comfortable story about how privatization saved the health of the public, they’ve forgotten their history, and are now owned by a private conglomerate that scarcely has public interest in mind, and charges people a premium for a public resource, and uses that money not to invest in safety, but to squander safety standards and actively undo the health of the public and the ecosystem at large.

St Johns Conduit served the people of Bristol well, functioning well into the 20th century, so that when the Bristol Blitz ravaged the city in World War II, the residents of the old city could continue to rely on it as their only operational source of water. If crisis hit again, could we rely on modern utility companies to extend their benevolent hand? Or would they simply continue posting bills through the rubble?

Sources:

- https://www.about-bristol.co.uk/wat-00.php

- https://www.southwestwater.co.uk/about-us/latest-news/transfer-of-bristol-water

- https://www.brh.org.uk/gallery/millerd.html

- https://collections.bristolmuseums.org.uk/collections/70f05c91-b793-3882-bca3-0301adc6d029/?s%3D%26filter%5Bcumulation.department.summary.title.keyword%5D%5B%5D%3DHistoric+Maps&pos=1

- https://www.bristolwater.co.uk/about-us/our-story/our-history#:~:text=An%20Act%20of%20Parliament%20was,via%20Temple%20Meads%2C%20a%20scheme

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_St_John_the_Baptist,_Bristol

- https://www.bristolwater.co.uk/about-us/our-story/our-history#:~:text=An%20Act%20of%20Parliament%20was,via%20Temple%20Meads%2C%20a%20scheme

- https://archives.bristol.gov.uk/records/17563/1/493

- https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/aug/09/public-could-receive-hundreds-of-millions-as-water-firms-face-sewage-lawsuit

- https://www.bristolwater.co.uk/about-us/our-performance/legal/company-information/#:~:text=On%201%20February%202023%2C%20Bristol,the%20Water%20Industry%20Act%201991.

Leave a comment